(Grateful acknowledgements to Fr. Paul Kramer for his book, The Devil’s Final Battle, from which many of the following quotations are taken).

The satanic revolution gains momentum at the Council

The word ‘revolution’ has been used numerous times to describe Vatican II. During the debate on the Liturgy Constitution at the Council, Cardinal Ottaviani asked, “Are these Fathers planning a revolution?”

Regarding the changes since Vatican II, Professor James Daly wrote:

It is one thing to pull off a revolution, quite another to do so and then have the gall to pretend that nothing “substantial” has been changed. It is not enough for our liturgical Robespierres to win; they must go on to claim that they never used the guillotine.[1]Revolution was apparent very early on. According to Anne Muggeridge (the daughter-in-law of the famous British Catholic convert and journalist Malcolm Muggeridge), John Cardinal Heenan of Westminster reported that when, during the rebellious first session of the Council, Pope John XXIII realized that the papacy had lost control of the process, he attempted to organize a group of bishops to try to force it to an end. But before the second session of the Council could open, Pope John XXIII died. His last words on his deathbed, as reported by Jean Guitton, the only Catholic layman to serve as a peritus at the Council, were: "Stop the Council; stop the Council." (The Desolate City)

Before the end of Vatican II, in February 1965, someone announced to Padre Pio that soon he would have to celebrate the Mass according to a new rite, in the vernacular, which had been devised by a conciliar liturgical commission. Immediately, even before seeing the text, he wrote to Paul VI to ask him to be dispensed from the liturgical experiment, and to be able to continue to celebrate the Mass of St. Pius V. When Cardinal Bacci came to see him in order to bring the authorization, Padre Pio let a complaint escape in the presence of the Pope's messenger: "For pity sake, end the Council quickly."

Several years after Vatican II, on April 12, 1970, Sister Lucy warned of "a diabolical disorientation invading the world and misleading souls". On September 16, 1970, she wrote to a friend in religion, Mother Martins, who had been her companion at Tuy, in the novitiate of the Dorothean Sisters. She had just been sorely tried by illness:

...I too, was not feeling very well in my heart, my eyes, etc.; but it is necessary to the Passion of Christ; it is necessary that His members be one with Him, through physical pain and through moral anguish. Poor Lord, He has saved us with so much love and He is so little understood! so little loved! so badly deserved! It is painful to see such a great disorientation and in so many persons who occupy places of responsibility...! For our part we must, as far as is possible for us, try to make reparation through an ever more intimate union with the Lord; and identify ourselves with Him that He may be in us the Light of the world plunged in the darkness of error, immorality and pride. It pains me to see what you tell me, now that that is going on over here...! It is because the devil has succeeded in infiltrating evil under the cover of good, and the blind are beginning to guide others, as the Lord tells us in His Gospel, and souls are letting themselves be deceived...This is why the devil has waged such a war against [the Rosary]! And the worst is that he has succeeded in leading into error and deceiving souls having a heavy responsibility through the place which they occupy...! They are blind men guiding other blind men...The "great disorientation and in so many persons who occupy places of responsibility" is a reference to the disorientation within the hierarchy of the Catholic Church.

Vatican II and the heretics

Bishop Helder Camara praised Pope John XXIII for his “courage on the eve of the Council in naming as conciliar experts many of the greatest theologians of our day. Among those whom he appointed were many who emerged from the black lists of suspicion.” In other words, from the censures and condemnations of Pius XII and the Holy Office. Heretics were among those advising and helping the bishops draft the documents of Vatican II.

Fr. Paul Kramer reported in his book, The Devil’s Final Battle:

On October 13, 1962, the day after the two communist observers arrived at the Council, and on the very anniversary of the Miracle of the Sun at Fatima, the history of the Church and the world was profoundly changed by the smallest of events. Cardinal Liénart of Belgium seized the microphone in a famous incident and demanded that the candidates proposed by the Roman Curia to chair the drafting commissions at the Council be set aside and that a new slate of candidates be drawn up. The demand was acceded to and the election postponed. When the election was finally held, liberals were elected to majorities and near-majorities of the conciliar commissions—many of them from among the very “innovators” decried by Pope Pius XII. The traditionally formulated schemas for the Council were discarded and the Council began literally without a written agenda, leaving the way open for entirely new documents to be written by the liberals. It is well known and superbly documented that a clique of liberal periti (experts) and bishops then proceeded to hijack Vatican II with an agenda to remake the Church into their own image through the implementation of a “new theology.’”[2] (p. 53)Two such theologians were Hans Kung and Edward Schillebeeckx. According to Chris Ferrara:

It was Schillebeeckx who wrote the crucial 480 page critique employed by the “Rhine group” bishops to coordinate their public relations campaign against the wholly orthodox preparatory schemas for the Council, which led to the abandonment of the Council’s entire meticulous preparations. Schillebeeckx was later placed under Vatican investigation for his outrageously heterodox views concerning historicity of the Virgin Birth, the institution of the Eucharist, the Resurrection, and the founding of the Church.[3]The liberals at Vatican II avoided condemning modernist errors, communism, and they also deliberately planted ambiguities in the Council texts which they intended to exploit after the Council. The liberal Council peritus, Father Edward Schillebeeckx admitted, “we have used ambiguous phrases during the Council and we know how we will interpret them afterwards.”[4]

Monsignor Rudlolf Bandas, a peritus at the Council, acknowledged that allowing suspect theologians at Vatican II (such as Schillebeeckx and Kung) was a grave mistake:

No doubt good Pope John thought that these suspect theologians would rectify their ideas and perform a genuine service to the Church. But exactly the opposite happened. Supported by certain ‘Rhine’ Council Fathers, and often acting in a manner positively boorish, they turned around and exclaimed: “Behold, we are named experts, our ideas stand approved”... When I entered my tribunal at the Council, on the first day of the fourth session, the first announcement, emanating from the Secretary of State, was the following: “No more periti will be appointed.” But it was too late. The great confusion was underway. It was already apparent that neither Trent nor Vatican II nor any encyclical would be permitted to impede its advance.[5]Fr. Paul Kramer writes:

In his book Vatican II Revisited, Bishop Aloysius J. Wycislo (a rhapsodic advocate of the Vatican II revolution) declares with giddy enthusiasm that theologians and biblical scholars who had been “under a cloud” for years surfaced as periti (theological experts advising the bishops at the Council), and their post-Vatican II books and commentaries became popular reading.[6]Yves Congar, one of the artisans of the reform remarked with quiet satisfaction that “The Church has had, peacefully, its October revolution.”[7] Congar also admitted, as if its something to be proud of, that Vatican II’s Declaration on Religious Liberty is contrary to the Syllabus of Pope Pius IX. He said: “It cannot be denied that the affirmation of religious liberty by Vatican II says materially something other than what the Syllabus of 1864 said, and even just about the opposite of propositions 16, 17 and 19 of this document.”[8]

Cardinal Suenens declared “Vatican II is the French Revolution of the Church.”[9] Cardinal Suenens may have been one of the cardinals indicated by Our Lady of the Roses, that would receive great punishment for his participation in the destruction of the Church. (Read more…)

Vatican II documents and sessions

As we stated above, Father Edward Schillebeeckx admitted, “we have used ambiguous phrases during the Council and we know how we will interpret them afterwards.”[10] The New York Times recognized these ambiguities: “The Council’s documents, shaped by the bishops and their theological advisers in four two-month sessions held each fall from 1962 through 1965, offer more than enough compromises and ambiguities for conflicting interpretations.” Fr. Frank Poncelot writes, “That there are ambiguities in the sixteen Council documents no one can deny. You can misquote its numerous paragraphs to prove or disprove many ideas, and this is frequently done to support liberal and devious schemes.”[11]

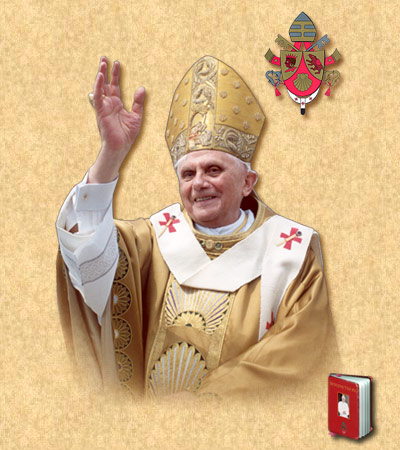

Cardinal Ratzinger observed that the documents of Vatican II, especially Gaudium et Spes, comprised a “counter syllabus” designed to “correct(!) ... the one-sidedness of the position adopted by the Church under Pius IX and Pius X,” and that these documents were an “attempt at an official reconciliation with the new era inaugurated in 1789.”[12] He also admitted that the Vatican II document Gaudium et Spes is permeated by the spirit of Teilhard de Chardin.[13]

Our Lady of the Roses, however, stated that Teilhard de Chardin is in hell:

"Many of Our clergy have become blinded through their love of worldly pleasure and riches. Many have accepted a soul once high as a priest. Teilhard is in hell! He burns forever for the contamination he spread throughout the world! A man of God has his choice as a human instrument to enter into the kingdom of satan. Man will not defy the laws of God without going unpunished. You are a perverse generation, and you call the hand of punishment down fast upon you." - Our Lady, March 18, 1973 (Read more…)

At Vatican II, Alfredo Cardinal Ottaviani was shocked to discover that a statement proposing that married couples may determine the number of their children was summarily added to the text of "The Sanctity of Marriage and the Family" without so much as a discussion as to its consistency with prior Catholic teaching. Cardinal Ottaviani asked:

...yesterday in the Council it should have been said that there was doubt whether a correct stand had been taken hitherto on the principles governing marriage. Does this not mean that the inerrancy of the Church will be called into question? Or was not the Holy Spirit with His Church in past centuries to illuminate minds on this point of doctrine?[14]Fr. Frank Poncelot writes:

Ecumenism means the modern movement toward religious unity, but false ecumenism is now one of the serious problems because of modernist elements in the Church and unauthorized modern theologians trying to “give away the store.” The sixteen documents of Vatican Council II are lengthy and “wordy”; many sections are ambiguous; they were not meant to make doctrinal changes, but opened the doors, unfortunately, for changes which were not intended. It authorized commissions to be formed with later became “open-ended,” especially when the dreadful word, “option,” became prevalent in the Council’s implementation. Well over 2000 bishops were present for all sessions and numerous observers (including non-Catholic) and the bishops’ periti. While there were ten Council Commissions, the liberal European alliance, controlled mainly by German bishops and their periti, quickly dominated the sessions and, with much behind the scenes work, influenced the direction taken by the commissions which were set up in the aftermath of the Council. These commissions “implemented” Vatican II and were responsible for interpreting the recommendations of the Council in their practical and pastoral applications. This is most important to note, because the great majority of the bishops present never intended most of the “implementation” that resulted, principally the Novus Ordo of the Mass—the Mass which was actually promulgated in 1970. The document from which liturgy changes came, Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy—first of the sixteen documents, ironically, is the most misunderstood Church document. Today we have Roman Missals almost entirely in the vernacular, whereas the Council document contains nothing about an all vernacular Mass, only that some parts of the Mass may use the vernacular, and ordered that the Latin language remain in the essential parts of the Mass. Further irony is that most Catholics today think that the Mass in Latin is forbidden, whereas the Council forbade the opposite—exclusive use of the vernacular.[15]Cardinal John Heenan of Westminster, a participant at Vatican II, explains in his book, A Crown of Thorns:

The subject most fully debated was liturgical reform. It might be more accurate to say that the bishops were under the impression that the liturgy had been fully discussed. In retrospect it is clear that they were given the opportunity of discussing only general principles. Subsequent changes were more radical than those intended by Pope John and the bishops who passed the decree on the liturgy. His sermon at the end of the first session shows that Pope John did not suspect what was being planned by the liturgical experts.[16]The liturgical expert Monsignor Klaus Gamber says the same thing in his book, The Reform of the Roman Liturgy, that the new liturgy would not have been endured at the Council:

One statement we can make with certainty is that the new Ordo of the Mass that has now emerged would not have been endorsed by the majority of the Council Fathers.[17]Richard Cowden Guido reported that many bishops were openly disillusioned with Vatican II at the Bishops’ Synod of 1985:

That there were misjudgments made at the Council no serious Catholic will deny. Following the Synod of Bishops in 1985, surprising comments were made by bishops who admitted this before leaving Rome. One author wrote, quoting another source: “… yet, delicately in public and more candidly in private, synod fathers acknowledged that Vatican II made two massive errors in judgment. The first was the vast over-estimation of the solidity of Catholic teaching and practice … the second error was an astonishing naiveté about the nature of the modern world.”[18]Vatican II and the failure to condemn communism

Vatican II even failed to condemn communism. Fr. Frank Poncelot writes:

… Vatican II was not called to suppress a particular heresy or problem in the Church. It overlooked the evil of Communism; it overlooked the spreading modernism with its Masonic ingredients that Pope St. Pius X condemned; and it did not address the problems that the electronic media could very likely cause for the Church worldwide.”[19]Fr. Paul Kramer reports that hundreds of bishops attempted to condemn communism at the Council, but their petition was mysteriously “lost”:

The written intervention of 450 Council Fathers against Communism was mysteriously “lost” after being delivered to the Secretariat of the Council, and Council Fathers who stood up to denounce Communism were politely told to sit down and be quiet.[20]Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre in 1983 told a Long Island, New York conference that it was he himself who carried the 450 signatures to the Secretariat of the Council at Vatican II:

And the Communists were promised, Communism will not be condemned at the Council, and it wasn’t condemned at the Council. I myself carried 450 signatures to the Secretariat of the Council in order to have Communism condemned. I did it myself! Four hundred and fifty signatures of bishops were put away in a drawer and they were buried in silence whereas sometimes the request of a single bishop was listened to. In this case, 450 bishops were ignored. The drawer was closed, we were told, no, no, we have no knowledge of that, there will be no condemnation of Communism. And they replaced the anti Communist bishops: Cardinal Mindszenty by Cardinal Lekai, Cardinal Beran in Czechoslovakia by Cardinal Tomasec. The same happened in Lithuania, and in Czechoslovakia, all the bishops became priests of the Pax movement, collaborators of the Communist regime. You can read in the book called Moscow and the Vatican how the Lithuanian priests wrote to their bishops a letter in which they say: “We no longer understand. Before, our bishops used to support us in the fight against Communism and they died martyrs, many are still in prison, others are dead, martyred because they supported us against the Communists in order to fulfill our duty as priests, and now it is you bishops who are condemning us, it is you who are telling us that we don’t have the right to resist, to fulfill our apostolate, because it is contrary to the laws of Communism, it is contrary to the government.[21]That the communists were promised that communism would not be condemned at Vatican II was effected through the Vatican-Moscow Treaty. Our Lady of the Roses said of this treaty:

Veronica - Our Lady is holding up a parchment of paper.Jesus also spoke on this treaty:

"Look, My child, what has been written down. From where and whence did this parchment of reconciliation with Russia originate, signed by many cardinals? O My child, My heart is bleeding.... The parchment of paper contains the words that made a treaty between the Vatican and Russia." (Our Lady, July 1, 1985)

"My child and My children, remember now, I have asked you to contact Pope John Paul II, and tell him he must rescind the Treaty, the Pact made with Russia; for only in that way shall you have a true peace." (Jesus, June 6, 1987)Vatican II: a pastoral, not a dogmatic Council

In Cardinal Ratzinger’s letter to Archbishop Lefebvre on July 20, 1983, he states that: “It must be noted that, because the conciliar texts are of varying authority, criticism of certain of their expressions, in accordance to the general rules of adhesion to the Magisterium, is not forbidden. You may likewise express a desire for a statement or an explanation on various points…. You may that personally you cannot see how they are compatible, and so ask the Holy See for an explanation.” Pope Paul VI himself also made a similar comment: “Given the Council’s pastoral character, it avoided pronouncing in an extraordinary manner, dogmas endowed with the note of infallibility.”[22]

At the close of Vatican II, the bishops asked Archbishop Felici (the Council’s Secretary) for that which the theologians call the “theological note” of the Council . That is, the doctrinal “weight” of Vatican II’s teachings. Felici replied: “We have to distinguish according to the schemas and the chapters those which have already been the subject of dogmatic definitions in the past; as for the declarations which have a novel character, we have to make reservations.”[23]

Regarding the novel changes and imprudent decisions that resulted after Vatican II, Dietrich von Hildebrand, praised by Pope Pius XII as the "20th century Doctor of the Church", instructs us:

In the case of practical, as distinguished from theoretical, authority, which refers, of course, to the ordinances of the Pope, the protection of the Holy Spirit is not promised in the same way. Ordinances can be unfortunate, ill-conceived, even disastrous, and there have been many such in the history of the Church. Here Roma locuta, causa finita does not hold. The faithful are not obliged to regard all ordinances as good and desirable. They can regret them and pray that they will be taken back; indeed, they can work, with all due respect for the pope, for their elimination.

"The great Council, the Council that has

brought forth discord, disunity, and the loss of souls, the major fact behind

this destruction was because of the lack of prayer. Satan sat in within this

Council, and he watched his advantage." - St. Michael, March 18, 1976

[1] Professor James Daly of

McMaster University, Ontario, The Catholic Register, October 12,

1977.

[2] Our Lady of the Roses Herself mentioned this “new theology” in

Her message at Bayside: "I allowed you, My child, to become aware now in full

measure of evil in the teaching institutions of My Son's Church. A new theology

of morals has been set among you. And what is it but a creation of satan!”

(Our Lady, January 31, 1976)[3]

Chris Ferrara, “The Third Secret of Fatima and the Post-Conciliar Debacle,” Part

3.

[4] “Open Letter to Confused Catholics,” Archbishop Lefebvre, Kansas

City, Angelus Press, 1992, p. 106.[5]

“Wanderer,” August 31, 1967.

[6] Most Reverend Aloysius Wycislo S.J., Vatican II Revisited,

Reflections by One Who Was There, p. x, Alba House, Staten Island, New York;

quoted in The Devil’s Final Battle, p. 53.[7]

Yves Congar, O.P. quoted by Father George de Nantes, CRC, no. 113,

p.3.

[8] Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Principles of Catholic Theology, Ignatius Press: San Francisco (1987) p. 42.

[9] “Open Letter to Confused Catholics,” Archbishop Lefebvre, Kansas City, Angelus Press, 1992, p. 100.

[8] Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Principles of Catholic Theology, Ignatius Press: San Francisco (1987) p. 42.

[9] “Open Letter to Confused Catholics,” Archbishop Lefebvre, Kansas City, Angelus Press, 1992, p. 100.

[10] Ibid., p. 106.

[11] Fr. Frank Poncelot, Airwaves from Hell, p.

187.

[12] Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Principles of Catholic

Theology, Ignatius Press: San Francisco (1987) pp. 381-382. [13] Ibid.,

p. 334.[14]

Fr. R. M. Wiltgen,

The Rhine Flows

Into the Tiber, TAN Books and Publishers

(1967).

[15] Fr. Frank Poncelot, Airwaves from Hell, pp.

143-144.[16]

J. Heenan, A Crown of

Thorns, (London, 1974), p. 223; quoted in Latin Mass Magazine, Spring

1996, p. 45.

[17] Msgr. Klaus Gamber, The Reform of the Roman Liturgy, p. 61.

[17] Msgr. Klaus Gamber, The Reform of the Roman Liturgy, p. 61.

[18] Richard Cowden Guido, John Paul II and the Battle for Vatican

II, Trinity Communications, 1986, the author quotes National Review,

February, 1986; quoted in Fr. Frank Poncelot, Airwaves from Hell, pp.

18.[19]

Fr. Frank Poncelot,

Airwaves from Hell, p. 186.

[20] The Devil’s Final Battle, p. 52.

[21] Conference Of His Excellency Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, Long Island, New York, November 5, 1983.

[20] The Devil’s Final Battle, p. 52.

[21] Conference Of His Excellency Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, Long Island, New York, November 5, 1983.

Quotations are permissible as long as this web site is acknowledged with a

hyperlink to: http://www.tldm.org